Duncan Murrell: The Story of a Whaleman and his Kayak

Humpback whale Bubble Feeding Behavior in Alaska, by Duncan Murrell

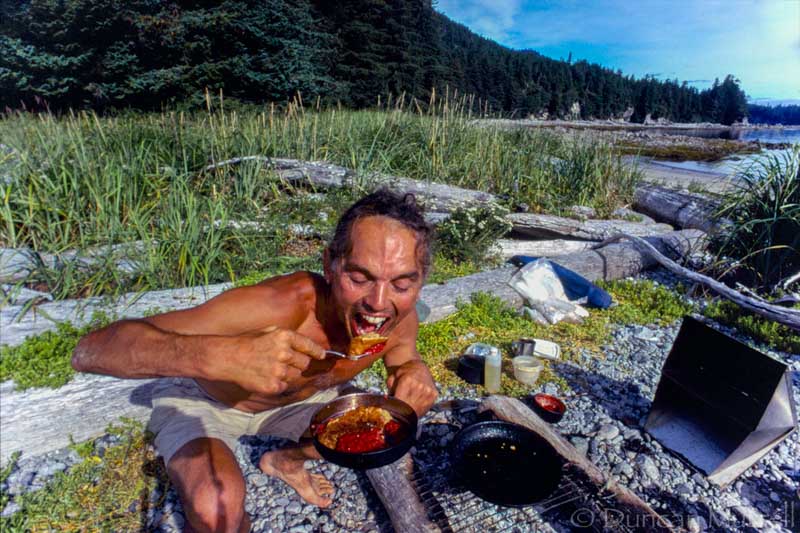

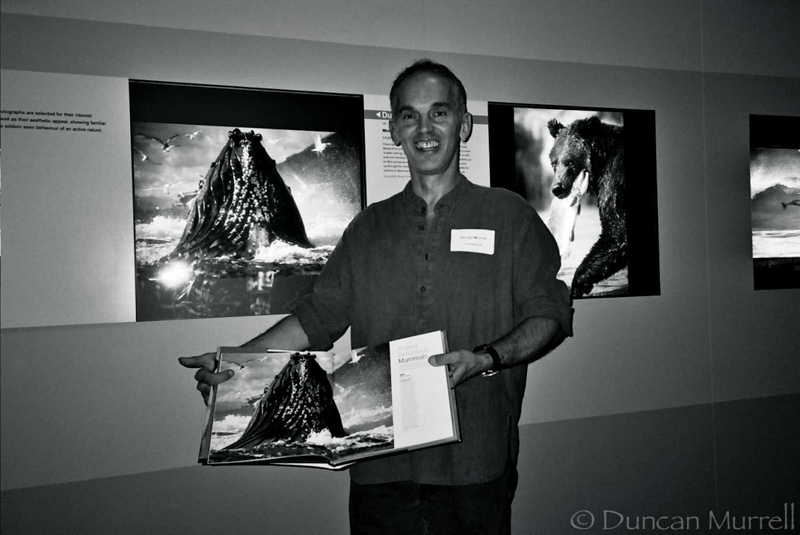

I first heard of Duncan Murrell while organizing our yearly Ocean Art underwater photography competition. The preliminary results were in, and Duncan had won “Best in Show” with his spectacular image of courting Devil Rays in Honda Bay, Palawan, Philippines. Yet, multiple attempts to establish contact yielded only silence. I couldn’t help but wonder how someone wins one of the world’s most prestigious underwater photography competitions but remains nowhere to be found. Eventually I found out why – Duncan had spent the past month living out of a kayak in the heart of Raja Ampat. Clearly, he wasn’t a normal contestant, or a normal photographer. No, Duncan is a whaleman. A chaser of whales, whale sharks, and all things in desperate need of conserving. And like his chosen objects of passion, he is migratory, constantly moving, and perpetually wet – a remnant explorer from a time when exploration meant true interaction on paths untraveled. Sans tour packages, constant livestreaming, Insta updates, or cushy liveaboards.

A Man Becomes a Whaleman

Originally hailing from Devon, U.K., Duncan began his journey to becoming the whaleman in one of the world’s greatest whale havens – Alaska. Flying to North America in 1978, Duncan became enthralled with the majesty of the humpback whale after a convoluted journey to Alaska involving an agonizingly slow hitchhike to Fairbanks from British Columbia, a bout of hepatitis in Mexico, sub-legal work at salmon canneries, a small wooden sailboat, and a pretty Norwegian-Alaskan girlfriend. Finding that photographing whales via kayak was the most effective and least disturbing for the animals, Duncan continued to accompany them on their seasonal feeding frenzies in the Inside Passage of Southeast Alaska. He dedicated years to watching and documenting the dramatically orchestrated ballet that is the life of a whale – particularly the bubblenet feeding behavior, which became his obsession.

An Orca Ballet

Four decades later, a slightly older and more wiry Duncan stares at me through a computer screen using technology that hadn’t existed when he first began photographing whales. He reflects on a life well spent and the environmental changes he’s seen in his global travels from Alaska to Madagascar to New Caledonia to Borneo to the Philippines and beyond. Facing a man who’d witnessed a lifetime of natural wonder, I couldn’t help but ask – what was his favorite experience? As I had hoped, almost immediately he had an answer: “The most memorable day I had in Alaska was when I was with sea lions playing around my kayak, as they always use to do. A big bull hung around, and then disappeared and swum beneath me. All of a sudden, it jumped up in front of me and made amazing eye contact with big bulging eyes. But 15 minutes later it disappeared and was being attacked by orcas! And then some humpback whales showed up and also got attacked by the orcas. I was right in the middle of all of it. I had orcas zipping around me and humpbacks on their backs, slapping their fins trying to fend off the orcas. I was just shaking with adrenaline, and I just thought gosh, it’s times like this when I wish I was with somebody to share it with.”

Trouble and Help on the Malagasy Coast

Having a deep propensity for adventure, Duncan has often found himself alone in his endeavors. Very few companions would have had the drive to keep up. He speaks of dreamier days, like owning a yacht in Alaska with a young woman in search of whales. But, often his story is one of a man and the sea. Duncan’s travels to Madagascar were perhaps the most emblematic of this story. It was a journey as the first person to kayak up Madagascar’s eastern coast that eventually led him to the halls of Buckingham Palace to meet the Queen.

“I had a near miss in Madagascar, on my very first day out. I was kayaking up the east coast and the swells in the Indian Ocean were just horrendous. It was getting late and I needed to land. When you’re kayaking in those places you’re checking the sequence of waves. But kayaking on the coral reefs was an absolute mine field. You’re surfing through the middle of a gap in the swell, and looking down, a coral reef is right under you. One moment it’s calm and then another bloody wave is crashing right over you. It can just suddenly explode with the surge…” On that first attempted landing Duncan’s kayak flipped with him and a month of supplies in it. “Fortunately, there was a guy on the beach who helped me save my kayak.” A recurring theme of Duncan’s stories is the selfless kindness of strangers. And perhaps that is why Duncan is never truly alone in his endeavours. Before long, Duncan was back on his feet and in his kayak, taking on the Indian Ocean swell in full force.

From Whales to Whale Sharks

Duncan’s ventures in the world of underwater photography began with another kind of whale. One that is actually a fish – the whale shark. As with the Alaskan humpbacks, Duncan moved his home base to Palawan, Philippines to be with the world’s largest fish. But it wasn’t just this large, majestic creature that captured Duncan’s attention – it was the ecosystem surrounding it.

“[The whalesharks] would be feeding with skipjack tuna. The feeding cycle is that the shark goes down and then up, driving the feed to the surface, and then the skipjack tuna come in. The water is boiling and there’s commotion, and the fish are jumping in the air. When you get underwater, tuna are like silver bullets flashing past you. What I like about whale sharks are their entourage – they create this whole ecosystem swimming around them – tuna, remoras, a convoy of fish. Mothership in the middle and these other fish around it. That’s what makes whale shark photography so exciting.”

A Memorable Courting Ray Ballet

It was on one of these whale shark trips that Duncan was in the perfect position to witness a very rare event – a courtship dance of Spinetail Devil Rays in Honda Bay, Philippines. This one encounter, in a quick flurry of “sexual abandon,” led to a beautiful series of photos that have placed in multiple international photography competitions. One photo was Duncan’s best of show, Ocean Art 2018 win. You can read the full story of the event here.

The Impetus Behind the Man

But the devil ray ballet does have a darker and more uncertain side to the story. As I speak to Duncan, he laments declining mobulid (e.g., devil ray and manta ray) numbers. Having helped spearhead whale and dolphin conservation efforts in the 80’s, Duncan now sees the same need for rays. As with many endangered animals, the Chinese medicine market has recently targeted mobulid gill-rakers with no proof of efficacy. Market demand has led to mass killing of these beautiful creatures.

So Duncan does more than just sit there and lament. He does what few of us do – he puts himself in the middle of it all. Beyond reaching millions of people with his photography and changing the global perception oceanic creatures – Duncan travels to the heart of environmental issues and helps in any way he can. After his experiences in Alaska, Duncan was funded by the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society to teach marine conservation in many schools in the UK where he became affectionately known as the Whaleman. His photos were used by all the major international conservation organizations for the save the whale campaigns in the 1980s and 90s.

One of the highlights of this effort is his work with the Borneo Nature Foundation. It is in such places as Borneo, in an effort to help with conservation, he faces his most hated foe – leeches: “Leeches are terrible, I hate leeches. The thing is you can’t relax. They’re stalking you and they’re so sneaky. You’re walking around looking at your hand and how the **** did they get there?! I was at a camp ground in Borneo – woke up in the middle of the night and feel a squishy thing and they’re like slugs. I hate them and they itch. I carry a container of salt and they drop off straight away. So yeah, I got that to look forward to when I go back to Borneo.”

Most recently, Duncan has been documenting the global plastic pollution crises in the heart of Raja Ampat, hoping that a media outlet might pick up the photos just to show the extent of the crises. Recently, he spent much of a trip watching kids on pristine Indonesian islands play with huge influxes of trash brought to their beach by wind and current.

So what’s next for Duncan Murrell?

As can be expected, Duncan has a lot planned around the corner. He will be spending his birthday in Komodo, enjoying his Ocean Art prize, and then kayaking in the area. He has an interest in traveling up-river and doing some more river photography. He will also be going back to Kalimatan to do more work with the Borneo Nature Foundation. Most of all, he’s excited to get a new portable air compressor to bring along on his kayak adventures and use it to “snuba” around.

Duncan’s Photographic Equipment and Philosophy:

“These days I use a Canon 6D mark II. I had a 5D mark II that got flooded in my housing. For my work its affordable. I use an Inon X-2 housing – small and compact – for me it’s ideal for traveling. I can take it in the kayak. A lot of my stuff is really for free diving and snorkeling. I use a fisheye lens and I‘ve got a 17-40mm lens in that housing. All my lenses are pretty batted around. My 17-200mm lens fell in the water; my macro lens too. My equipment gets a real bashing. Sand, salt, humidity, that’s been the essence of my photography lifestyle.”

“A lot of my technique is being in the right place at the right time. Reflexes. I don’t do burst. I choose the moments I take the photos. I do a lot of wide-angle photography and vary my angles a lot. When I teach people photography – I tell them the world doesn’t exist just at eye level. I’m always getting really high angles with my fisheye lens. I do love using my fisheye. I really enjoy people, groups of people, crowds, and then the same underwater. I haven’t really gotten into macro photography underwater. I’m always looking for obscure angles on things.”